I’m currently at Kwantlen Polytechnic University (KPU) as their Indigenous Journalist in Residence, and in addition to journalism work, I’ve been speaking to some of their other classes about Indigenous subjects.

Last week I spoke to their Geography class to talk about how First Nations land works from a planning perspective. I’ve worked on my First Nation’s lands advisory committee, done consultation work, and done reporting on some issues related to this. I am by no means an expert, but I know enough to give you the big picture summary of it.

Slide 1: Native land is a bunch of different things:

Here in the Coast Salish region, we have 5 different legal regimes over our land. The first is Traditional Territory. It’s a term I don’t like because it makes it sound like it’s in the past and we don’t use it anymore. That’s wrong, and I’ll come to that in a bit. But Traditional Territory are those giant blobs of colour beyond the reserves that you see on maps like the one on https://native-land.ca and on similar sites. When you do an acknowledgement, 99 times out of 100, this is what you’re talking about.

Non-Natives often see this land as fully alienated from First Nations.

Next are Reserves. You probably know that there are more than 600 First Nations in Canada, but you might not know that there are more than 3000 reserves in Canada. First Nation and Reserve are not synonymous - some nations may have more than one reserve. At least one nation has none (which is more than it deserves, I’ll explain another time). Reserve land can be administered under Land Code, under the Indian Act, or parts of it are held by Certificates of Possession.

Land Code

This is the legal regime created by the First Nations Land Management Act, a federal law that exempts participating First Nations from 34 sections of the Indian Act relating to land. If your First Nation votes to join the FNLMA regime, you need to create a code for it, and a body to govern it, and bylaws to manage it. Once you do that, you’re fully in control of it, and are responsible for zoning, taxation and everything else to do with your land. One thing, is that if you do choose to go Land Code, you don’t need to include all of your land, you can agree to leave some land under the Indian Act - something my First Nation has done for one of our reserves which the feds leased out to industry and have ruined with pollution. If we take it over under Land Code, we have to pay for the clean up. If we leave it with the feds, it’s their problem.

Indian Act

For those Nations that don’t go Land Code, they remain subject to the 34 sections of the Indian Act that govern land. The reason this is a bad thing is that the feds have shown that they don’t care, don’t manage things reasonably, and are too slow to keep up with the needs of businesses that want to work with First Nations. Behind every piece of heavily polluted reserve land, every unfair lease that alienates our land to non-Natives for $1 a year, there’s the Indian Act.

The thing is, to run Land Code, you need to get a vote passed in your First Nation (where all politics is populist), and you have the resources to actually run it.

Certificates of Possession

You know how they say there is no private land ownership on reserve? Certificates of Possession are private land ownership - though one where you can only transfer it to a member of the same band. For planning, it’s seemingly ad hoc.

Lastly there are the non-reserve private lands. These are properties off reserve that are owned by the First Nation. Technically, they are owned the same as any other fee simple property that any other Canadian owns. Technically. In reality, at least in these parts, that’s not the case. Because the relationship your First Nation has with non-Native government means that you could get preferential treatment with this land, and rapid approvals for development. I have a friend who does development for a nation and they got a massive skyscraper through approval in something like a year.

There’s also the possibility of converting these off-reserve lands into reserve lands using the ATR process, but that’s an area where I don’t have much experience.

Slide 2: So that what Native land is, here’s how it works:

First Nations land use planning is actually very similar to off reserve planning. When I served on that lands committee, whenever we held a meeting it felt like being in a scene from Parks and Recreation.

And the end product is mostly the same, and can be seen in First Nations Land Use Plans such as this one from Tsleil-Waututh. That land use plan is a great example because like many First Nations it has one or two deviations from land planning in the rest of Canada. For Tsleil-Waututh, it’s this:

Slide 3: Land for the descendants

That is a unique form of land management - one I proposed for my First Nation (and that has been integrated into our planning). Looking at planning, you’ll see a lot of standardization, but also there’s usually something distinctive that reflects the culture of the nation and their relationship to land.

In this case, for us Salish people, this fits with our understanding of land ownership, and rights to it. This is land on reserve which we’re further reserving for future generations to decide what to do with. You might think that sound like a land trust - but it’s not.

Slide 4: Land trusts (I’ll skip explaining this part so your head doesn’t melt with boredom, and move on to traditional territory below this pic).

Slide 5: Traditional Territories

You hear ‘tradition’ and you think of stuff that happened in the past. Traditional territory does not mean that. Yes - much of it has been alienated in some ways from us. Taxation power, planning, and zoning have been taken. Some key properties have been seized. But no matter what has been done, we have not given up control. Here are a few ways we [Slide 6] continue to exercise authority over our territories:

We still access resources on our territories, in many cases, on an industrial scale. For example in Slide 7 you’ll see off reserve lands which are used for forestry by my First Nation and our neighbour, Katzie:

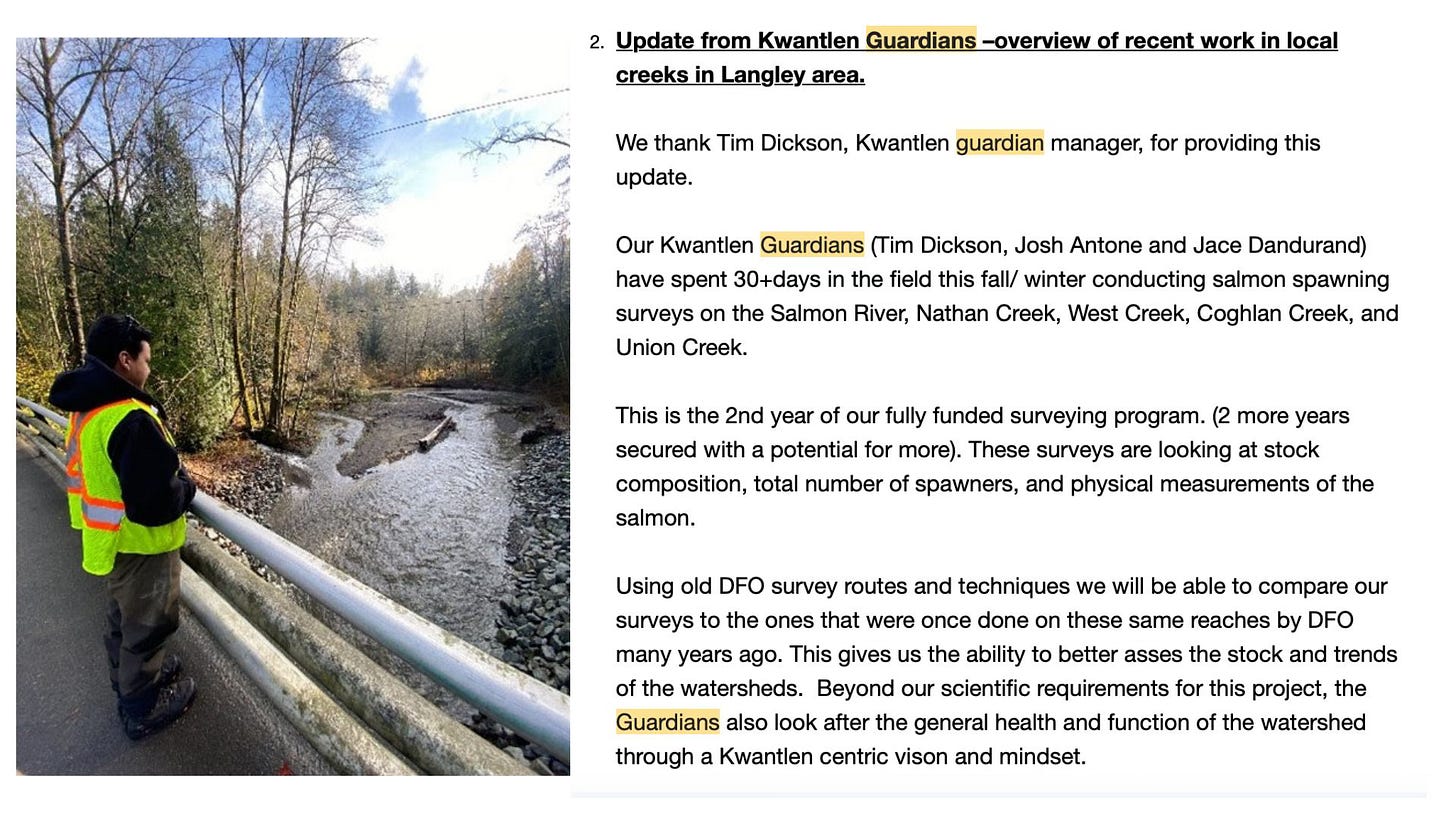

You also have Guardian Programs where our people go out onto the land throughout our territory and demonstrate our sovereignty by conducting surveys, overseeing construction, order remediation work where needed, and enforcing our land and resource management rules. Here’s an example of our Guardians’ work in Slide 8, from my First Nation’s weekly newsletter:

As our resources grow, some nations are also looking at ways of extending land use planning off reserve and into the entire ‘Traditional Territory’. Here’s an early example from the Fraser Valley in Slide 9 where the local First Nations have described their land use priorities and concerns outside of reserve:

And that brings me to the last slide. Above we’ve talked about how First Nations land works. Here’s how I’d like to change it, so that it works better for everyone. For my First Nation, I’ve proposed that we take planning a step further and zone the entire ‘Traditional Territory’.

In Slide 10, we looked at the benefits of doing this:

The Duty to Consult has actually been a burden to First Nations. There are too many inquiries to deal with, too many meetings, too many reports to write. If you wonder why working with First Nations is slow, it’s because of this complexity and these huge demands on our time.

Zoning has been used for a long time to make life harder for minorities, and to alienate land from First Nations. If we take control of zoning, we co-opt that power for ourselves to take our land back in a very meaningful sense, create predictability and fairness, and encourage more investment and development on our lands.

The solution I propose isn’t simple or easy - moving zoning into the Traditional Territory will require us to account for another 2 or 3 types of land holding, but we already have 5, so it’s less of a hurdle than you might think. But in the end, it’ll make things simple, fast, efficient, and will take all that money that goes to consultants and lawyers, and the staff who have to answer to them - and give half of it to First Nations, and half back to the people doing development.